02 February – 26 March 2022

Barcelona

know more about

MOTHER-MAKING AND THE SHEDDING OF TIME

By Lorena Munoz-Alonso

In the studio, in a storage room, the sculptures stand like a cluster of beings huddled together, waiting. When Eva Fàbregas opens the door and turns on the light, I see them on the floor and half expect them to talk.

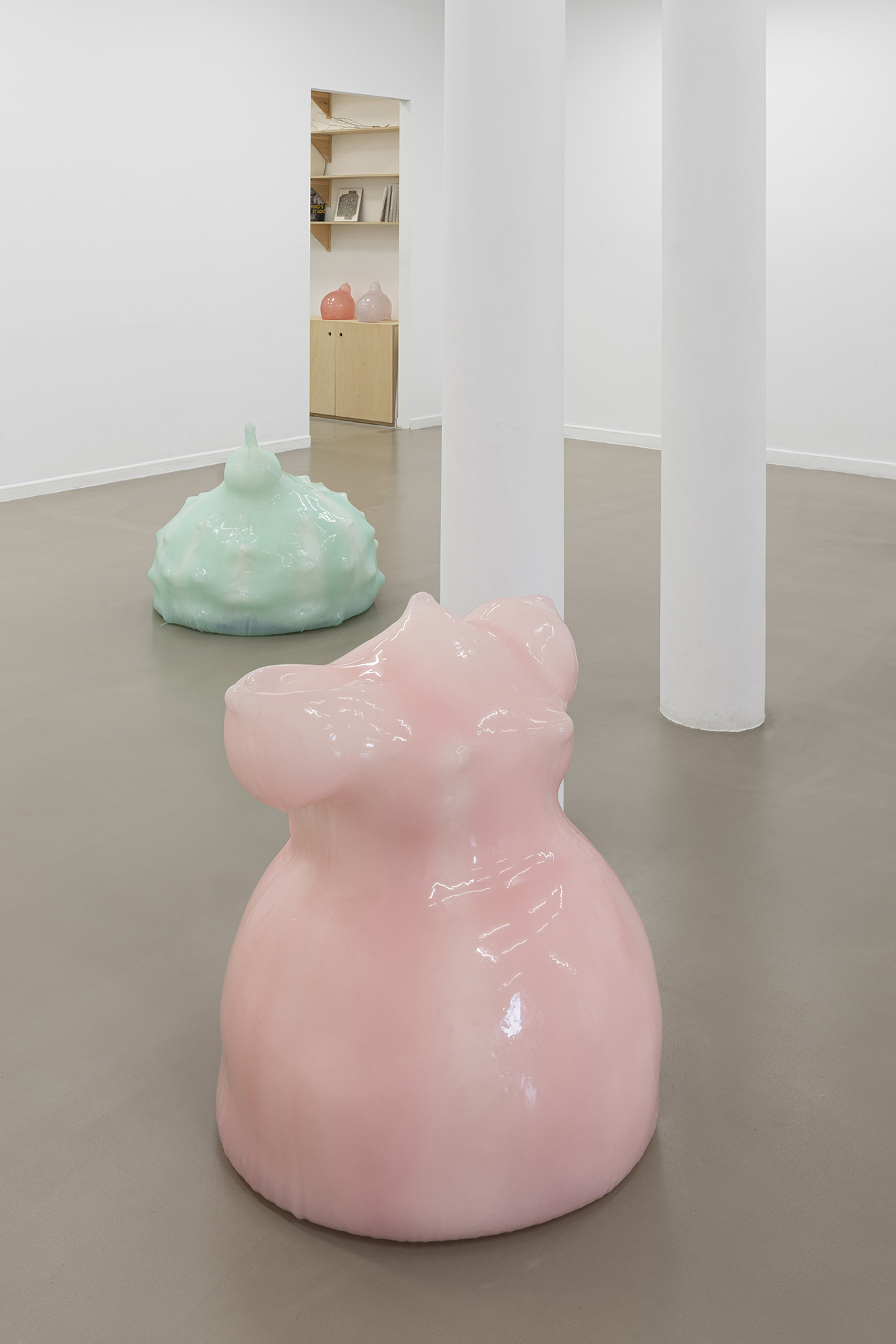

Their biomorphic shapes ooze a strong sexual innuendo. They tease me with their cheeky interplay of deceptively-hard-yet-soft surfaces, of pointy limbs and round ends in bright colours, so redolent of gonads. They reek of erotic possibilities, of fluids and desire. It feels explicit, so I’m immediately suspicious of their manifest directness, their intelligibility. What else lurks in the playful, colourful sculptures that the artist is presenting in “Vessels”?

* * * *

Some of these sculptures (or should we say characters?) have been named Sheddings (2021). I think of the word and realise there is something inevitably bodily about it. Stuff that sheds tends to be alive and kicking; animals namely, be it humans, domestic or wild. The stuff that is shed is organic, like particles of human skin or the relentless tufts of dog and cat hair. Fluff balls growing on corners of houses and apartments, gathering dust as they roll, like microscopic avalanches. Dust is composed of sloughed-off skin cells, hair, lint, bacteria, dust mites, bits of dead bugs, soil particles, pollen. All these components have, at some point in their life cycle, been shed. I think of a snake writhing, slowly shedding its skin whole, as grotesque as it is fascinating. I think of a condom quickly coming off a penis. I look at Fàbregàs’ silicon sculptures, filled with bubble wrap, dildo-esque. Sheddings, remnants, traces.

The more I think about it the more I suspect the sculptures’ explicitness, their archetypical quality—a combined phallus with a breast, or a single testicle attached to a womb-like cocoon—belie a much more complex, paradoxical dynamic.

In their presence, I’m taken over by sense of childlike joy dripping with naughtiness and trepidation. The titillation of a small girl transgressing something she doesn’t yet understand. The conflicting emotions that are intimately connected to the discovery of infantile sexuality, of a world of bodily pleasures still out of reach and understanding, yet to be fully apprehended, tested and mastered, and thus only approximated by mimicry.

When I put to her all this Fàbregas resonates with my reading, but feels her work seeks to convey something perhaps more maternal and grown up; something about bodies that are able to gestate and birth, nurture and hold. This makes me think of the painter, psychoanalyst and feminist theorist Bracha Ettinger, who coined the term “matrixial space” in the 1980s to designate the creative potential that all human beings, both women and men, have and that when nurtured can result in gestating-like processes such birthing or artwork. It makes me think of the symbolic womb we all have, regardless of sex or gender.

* * * *

I can suggest several readings, hopefully open up lines of thinking about these particular works. But when it comes to deciding which one sounds more accurate to the artist herself, she doesn’t quite know. And, of course, neither do I. I think this is because there’s something about Fàbregas’ body of work at large that defies language. It inhabits the realm of the senses, invoking a pre-linguistic stage that eludes transformation into verbal representation. I feel her work belongs to the world of the somatic, the guttural, the experiential, the unnamable.

There are other, more prescribed avenues from which to approach it, of course. From an art historical point of view, it would be fair to suggest that Fàbregas’ highly sexualised oeuvre treads on the legacy of a group of seminal artists practicing in the midst of the second wave of the feminist movement in the 1970s. Through photographic self-representation as well as sculptures and paintings depicting genital shapes—mostly breasts and vaginas but also penises—artists like Renate Bertlmann, Hannah Wilke, and Judith Bernstein sought to convey an ecstatic estate of gender liberation, embracing a hitherto denied entitlement to female sexual expression, domination, and pleasure. This represented a huge aesthetic leap towards a kind of radical sexual figuration, which was rather different in tone to what some excellent female artists had been producing just a few years earlier. I’m thinking in particular of the “eccentric abstract” work of Eva Hesse, where genitalia is alluded or hinted at rather than portrayed, and of Nikki de Saint-Phalle’s joyful and more concrete celebration of womanhood in her sculptural series of Nanas—although the visual lexicon of both artists is germane to the understanding of Fábregas’s practice in important ways too.

* * * *

Like the work of artists working in this tradition, Fàbregas’ work revels in a sense sensual (and sexual) exhilaration. The artist tells me that when she started working in the studio on what eventually became these sculptures, she had this notion of the phallic in her head: the architecture of the dildo, its bright colours and tantalising forms. But that’s not the symbol that haunts her travails anymore, she says. Instead, she finds herself wanting to work on a scale that can almost replicate hers, creating a cohort of silicon twins and wanting to touch and get parts of her body inside them, fill their cavities, and make them fill hers. A double-way penetration.

To me these sculptures seems to me to be less about intercourse, about two separate parts coming together, than about the phantasy of hermaphroditic omnipotence, the possibility of self-satisfaction and/or self-reproduction. This sexual ambiguity opens up a space of potentiality where anything could happen and any part could serve any genital purpose, therefore foreclosing the need to copulate with external components. The sculptures become self-sufficient, emancipated both from Fàbregas as mother-maker and from their consumers, shirking the expectations placed upon them according to the phantasies of the public: to be soft and warm to the touch, or to be hard, to be penetrated or penetrate, to be arousing, to be entertaining. It is then that we can see their opaque, frustrating and slimy aspects. The works are fun and joyful on first instance, yes, but they also refuse to deliver. They tease and arouse and then frustrate our (in)flamed desires.

* * * *

Since I saw them at the Fàbregas’ east London studio, I’m fascinated by her Vessel (2021) pieces, which now hang on the walls at Bombon Projects. The spheres, made of latex, resin and lycra have an opening, a cavity, from which a trail of felt pours out, like fluids from a gaping wound, or milk from a breast. In some pieces it functions like a connective tissue, bridging two spheres. The sculptures are beautiful and abject. The materials, however, will no doubt decay. But ephemerality doesn’t concern her, says Fàbregas.

On that rainy afternoon at her studio Fàbregas tells me that she travels with her sculptures. That they are foldable, so she can empty their fillings, fold them and put them in a suitcase to take them with her. She demonstrates this to me and there is so much love in the way she handles them. When I tell her this, she says her sculptures are her children, that there is an exuberance of maternal instinct that, for now, is fully expressed and realised in her work. I tell her that perhaps that is why temporality is so fundamental in her work. That if they are (like) children, they are destined to first become and then decay, following the arc of life. And birthing children into the world, fertility, is also an event ruled by temporality, only possible, or at least probable, within a certain window of biological time. (Although, does that, with the reproductive technology advances of the transhuman era, still hold true?).

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso is an art critic and psychoanalyst in training based in London.

Read More