11 April – 01 June 2019

Barcelona

know more about

Our relationship with objects and the symbolic value we give them is a topic that is common to all contemporary artistic production, which in turn is a reflection of pre- industrial times, before the mass-production of objects. During the 20th century, the work of art, an expression we normally use to define an object with artistic value — a made object, a document, or an action — was seen as an attempt to objectify and materialize the shapes and forms that come to our mind, which we know are impossible to translate into an object. Still, objects are the closest thing there is to our desire of understanding and transforming the world. Our gaze upon nature, reflected in the different ways we represent it, is the first of the forms we have of objectifying the world. The appropriation of all the resources of nature and their subsequent manipulation and transformation is even more visible in the field of science and in scientific advances.

What happens in a laboratory where we study a certain object in a controlled and isolated environment has direct consequences in all other areas. As we manipulate things, we become objects ourselves. Today, we are all treated as merchandise, warped by the rules of the neoliberal market, we are points of energy, receptacles and channels through which objects, images, texts, and information manifest and materialize. In this process of mechanization, we have objectified ourselves, making us obsolete. Maybe because of this, works of art — in their essential counter-function, their apparent lack of meaning — are the objects we need the most. They are the flaw in the system, the thing that has no function other than to remind us all that the world is more than just scientific reasoning, that it is also empirical thought. That the world is about more than facts, that it includes sensorial experience, the shapeless and the unusual — a place where we need to create a new function, a new language for the objects we are unable to classify.

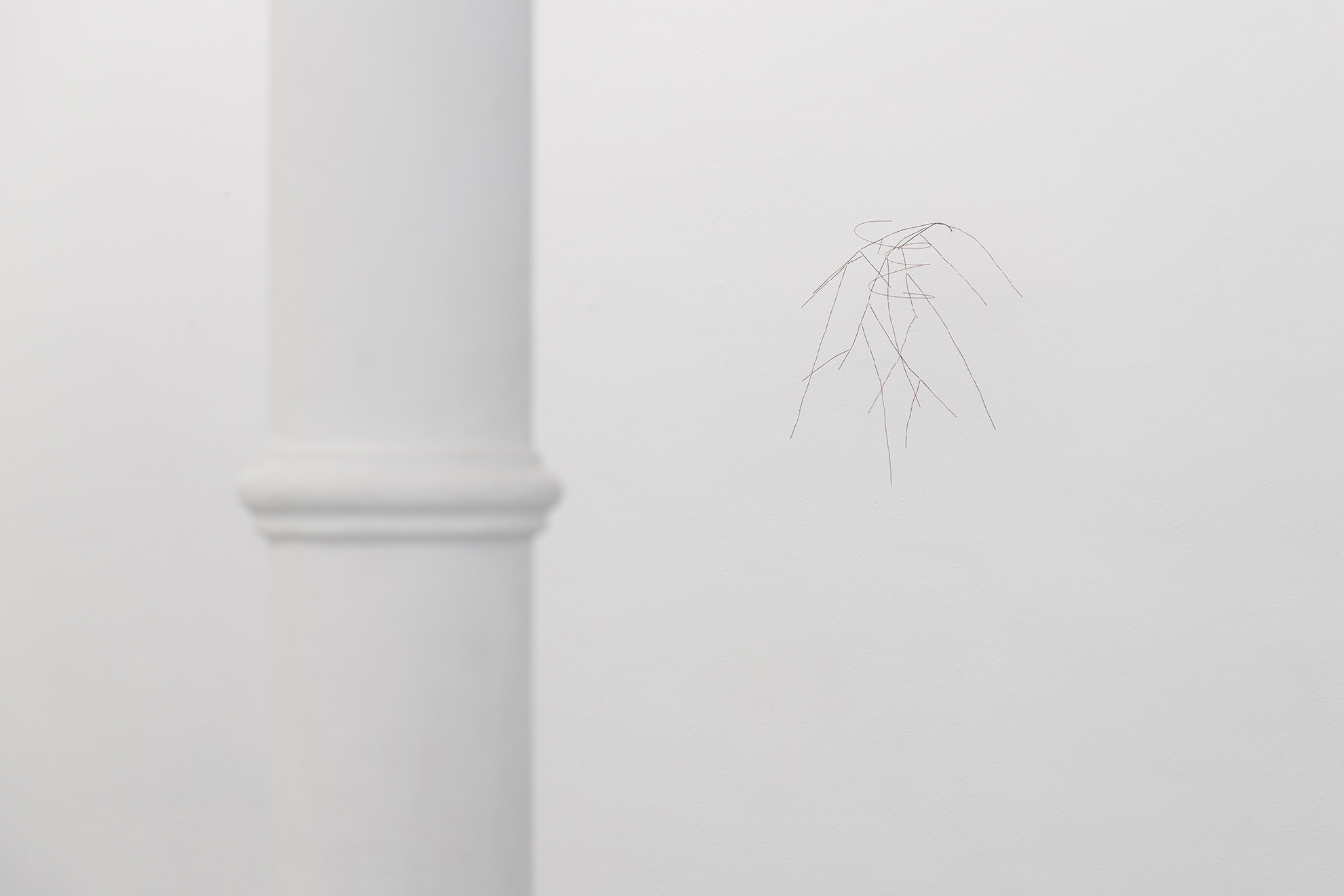

The precision of each of the sculptures created by Joana Escoval makes them objects that are simultaneously form and action, material and immaterial. It is as if each one of the pieces is going through an internal struggle we do not have access to.

The form and the action exerted by the matter appear side by side, with no hierarchy. The pieces need to have a final form, it is necessary to present them as finished, but they are still changing. And this form that the pieces ultimately take corresponds to the non-formal characteristics that precede them. It may seem confusing, but it is not.

The use of certain metals, such as gold, silver, or copper, or a new alloy in which we can find these elements, is essential to the understanding of her work, because these metals have chemical components that blend with ourselves without us noticing it. Scientific and historical data help us understand the developments of molecules, the atoms that make up all bodies and objects, all matter. As with other things, metal is in constant mutation and communication. The chemical and alchemical processes these sculptures are subjected to are part of their creation process. When the artist decides to smelt a certain metal, she transforms a certain matter, and, while it passes through different states, she allows it to absorb and to entrench itself in the environment that surrounds it.

We know that, in their final form, metal objects outlast many other objects. Maybe some of the properties of the gold that was used by the romans, which is on display in so many museums around the world, but also other metal objects from different cultures, are still spreading their properties, not only in their formal appearance but also through their chemical properties. Maybe metals have physical properties that allow them to absorb a part of the person who wears them, or of the persons they share their lives with — something that is manifested not just through their visual presence, but also by their alchemical properties, invisible even under the microscope. In her book, Vibrant Matter, in a chapter with the title A Life of Metal, political theorist Jane Bennett — known by her research on nature, ethics, and affection — tells us that, in metals, the space between each atom, the void between them, is as important as the atoms themselves. Bennett quotes Manuel de Landa and his idea of “complex dynamics of spreading cracks.” Bennett also refers to the spiral feedbacks that exist between the “idiosyncratic movements of their neighbors, and then to their neighbors’ response to their response.” (…) “The dynamics of spreading cracks may be an example of what Deleuze and Guattari call the ‘nomadism’ of matter.” In the first pages of her book, Bennett writes about the differences between objects and things. Objects are how they present themselves to a subject, this is, with a name, an identity, a shape (gestalt); things, on the other hand, signal the moment objects become the Other, when objects answer back.

The work of Joana Escoval escapes the categorizations we so often try to find, or even fake, as we attempt to communicate and understand the work of an artist. We ow these processes of categorization to science, or to an idea of reasoning inherited from the Enlightenment that has since then been shaping Western thought, that I prefer not to bring here on purpose. It is not just a question of trying to find an historicist perspective of her work, but, as I have already stated, it is important to look upon the matter and the chemical properties of the pieces themselves, because this is a way of accessing the work that, although quite concrete and specific — materialistic, if we will — makes it impossible for us to forget that this materiality includes a notion of time that is essential to include in our analysis. The notions of time and scale — and I am not referring to the size of the pieces, but to their temporal scale — transform Joana Escoval’s sculptures into tools to measure time. While escaping these excessive categorizations, her work can be understood under the light of the concept of immanence, a suspension of time, which is contrary to contemporary production and to the obsession with history and how to capitalize on works of art. Some of the pieces created by Joana seem to have been made two centuries ago, or objects that come from the future. Because of the materials she uses and the forms she produces, her sculptures are often places of passage, or refer to an object used in a ritual, vestiges of an event, of something that is right in front of us but that we can only partially see, because of a time difference between us and the object. Notwithstanding, her work is about the present, and about the ways it exists and propagates through us.

Pedro Barateiro

Read More