10 October – 06 December 2019

Barcelona

know more about

The more we use things, the more we become like them. Machines are human, they are as equally composed of screws as they are of calculations, equally made of engine and engineering. We make technology in our likeness and we think of it as part of ourselves: it’s already replacing us, we’ve already become one. The tricked-out car doesn’t look like the owner as much as the owner looks like the car. We imagine technology and then technology makes us imagine as it. We think of time in the shape of a wheel, in the shape of a car or in the shape of an airplane. The emblem of an obsolete speed, the car is the machine that still roots us to the ground, that makes us feel the bumps in the road and makes us look out the window at the changing landscape. It’s the beginning of accelerated time, but it’s still a mobile home[1] at 1:1 scale, a domestic bubble that moves through space. It is the opposite of the aircraft, which homogenizes everything making it small in the distance, which takes off and lands in places that are not even places, without anything happening in the in-between. In incorporeal times, the car still connects us to the age of the assembly line and the workshop and the parking garage. In the myth of living machines, cars are the first to rise against their owners, transformed into crude and curt robots.

In ancient theater, the term Deus ex Machina was born to describe the device used to bring actors playing gods into the scene, creating an illusion of flight or apparition. Later, it is used to describe a strategy, also a device, but a narrative one, which introduces a change so unexpected to the plot that it appears unlikely[2]. Devices, apparatus, tools, or mechanisms, are as much inert as they are alive: social, historical, political, small and large machines are composed of organs and organized intelligence systems. Theater operates on the premise of illusionism, creating an autonomous time and space zone where things, which aren’t really there, appear real to the audience.

It occurs that within the limits of the stage nothing is just what it is, but everything that it can seem to be. The value of that illusion lies only in the body of the actor, which contains the possibility of talking, acting, performing. Possibility is the most immaterial thing that can be governed: the abstract machineries of political economies govern bodies and their powers.

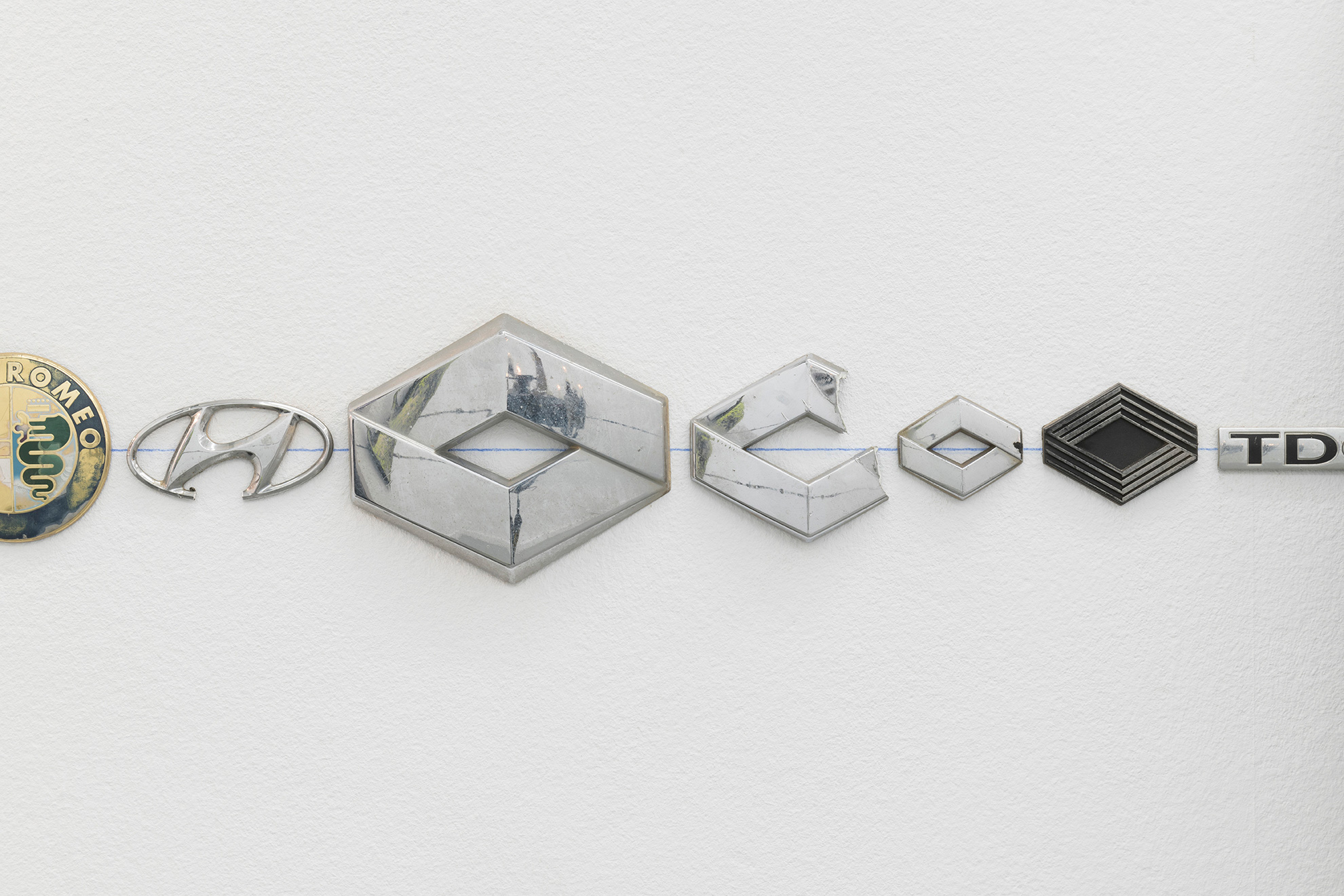

In Return of the Junker. JM 2000, the main character is absent, it is a ghost, a mortal machine, a body that’s been exploded into all of its possibilities. More than that, a car is a lethal machine, an ever-latent accident, the potentiality of a disaster being activated at every instant. Here, the machine is a technique, an effect, a trick: a twist that resolves the act. Turned into a face, a painting, a domestic item, or a workshop, its personalities manifest themselves in every transfigured fragment. In an inverse modification, it comes back from the junkyard to recompose itself in the hands of the artists, dressed with an auto-mechanic’s coveralls and a magician’s hat.

Sira Pizà

* Created at the family’s welding workshop of one of the artists, Return of the Junker. JM 2000 is a collaboration between Josep Maynou and Jordi Mitjà produced in the area of L’Empordà between spring and fall 2019.

[1] Jean Baudrillard starts his chapter“Addendum: The domestic world and the car” describing cars in his book The System of Objects. In the Spanish version of Siglo XXI Editores, Madrid, 1999.

[2] Gerald Raunig talks about it in the chapter “Theater Machines”, in A Thousand Machines, A Concise Philosophy of the Machine as Social Movement. Semiotext(e), MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2010.

Read More